The following content is developed for children with severe asthma. Consider in conjunction with the adult Medications section

Severe Asthma Medications in Paediatrics

Severe asthma is defined based on on-going respiratory symptoms despite ‘high dose’ conventional therapy. The definition of high dose treatment differs for children, compared to adults. Relative corticosteroid doses for children are available in the Asthma Australia Handbook

| Inhaled corticosteroid | Low Daily dose (mcg) | High Daily dose (mcg) |

| Beclometasone dipropionate | 100–200 | >200 (up to 400) |

| Budesonide | 200–400 | >400 (up to 800) |

| Ciclesonide | 80–160 | >160 (up to 320) |

| Fluticasone propionate | 100–200 | >200 (up to 500) |

Note: use of ‘high’ dose ICS (i.e. above 400mg beclomethasone/800mg budesonide/400mg fluticasone) has been associated with adrenal suppression and death. See “Systematic Corticosteroids” below for notes on screening.

Note: Severe asthma which is truly treatment-resistant does exist, but is very rare in children.

Common Causes of Treatment Resistance

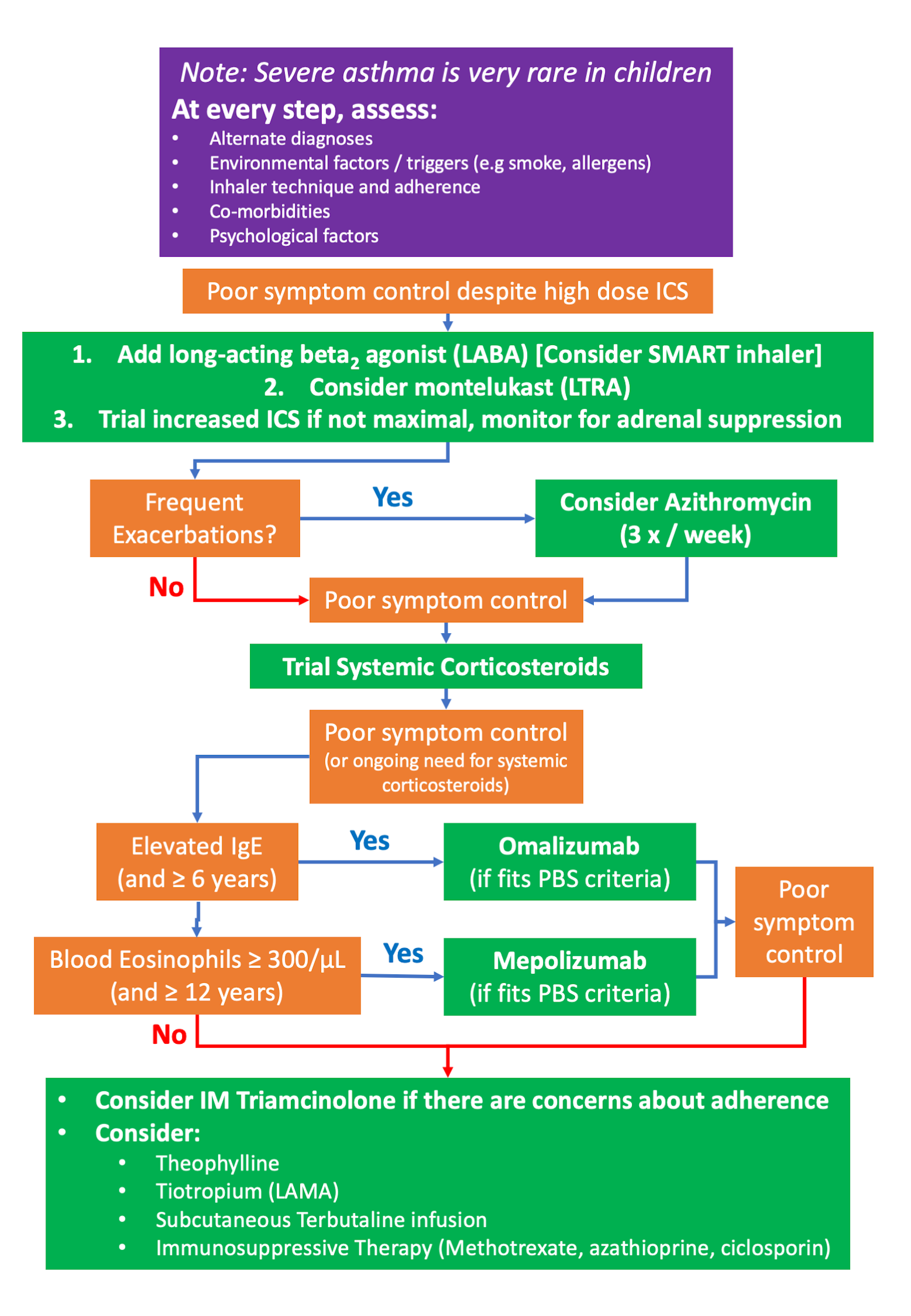

We recommend the following treatment approach in a paediatric population:

Add-on Treatments & Considerations in Paediatrics

SMART inhaler (Symbicort - budesonide/eformoterol)

- Provides both reliever and maintenance therapy

- Only licensed for use in children ≥12 years

- Very few clinical trials have been performed with children

- Trials of previous Symbicort formulations and dosages were safe and reduced overall symptoms and severe exacerbations (Bisgaard et al. 2006, Chapman et al. 2010).

- There is little information to guide capped dosage limits in children, for use as a reliever medication. The smallest possible dosing inhaler (50/3) should be used and capped limits are at the discretion of the treating physician

Anti-Fungals

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is very rare in children, but sensitization to mould is more common in severe asthma (Bush et al. 2010).

- Mould sensitization (particularly Alternaria spp) is associated with increased risk for very severe exacerbations and “brittle asthma” (O’Hollaren et al. 1991).

- Literature is lacking, but treatment with itraconzole and voriconazole may be useful in children heavily sensitised to moulds (Bush et al. 2010).

Macrolide Antibiotics (Azithromycin)

- Evidence is lacking to support routine use in asthma in children, let alone severe asthma

- Concerns exist about broad use contributing to macrolide antibiotic resistance

- Emerging evidence demonstrates utility in those with frequent and severe exacerbations:

- In young children <3 years, azithromycin is useful in shortening length of hospital stay (but it is possible that many of these children had bacterial bronchitis or mycoplasma) (Bisgaard et al. 2014, Bacharier et al. 2015).

- Azithromycin is given 3x/week or 2nd daily 10mg/kg to a maximum of 500mg

Systemic Corticosteroids

- Commonly used dosing: 1mg/kg oral prednisolone daily or 2nd daily. Treatment duration will depend on need, but durations of >2 weeks of oral steroids require weaning regimens.

- Alternative options include a trial of IM Triamcinolone injections, which may be useful in diagnosing steroid resistance if there is a suspicion of non-adherence:

- Dosages: Initial dose for children is 40 mg, which should be given by deep IM injection into the gluteal muscle

- Doses may be repeated at intervals ‘‘according to patient response,’’ and may be adjusted up to 100 mg

- Children <10 years old were limited to a single dose, and older children to no more than 5 doses (Panickar et al. 2005).

- Ongoing monitoring should include: BMI, blood pressure, blood count, glucose (FPG, A1C, 2-h OGTT or casual PG), lipids (LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, non-HDL-C, TG, ± apo B), and bone mineral density (BMD)

- Screen for adrenal suppression (e.g. 8-9 a.m. cortisol or synacthen test) when:

- Patient has received systemic corticosteroids for: > 2 consecutive weeks, >3 cumulative weeks in the last 6 months, or when concerned about long term high doses of ICS

- Patient has persistent symptoms of adrenal suppression: Weakness/fatigue, malaise, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, headache (usually in the morning), poor weight gain and/or growth in children, myalgia, arthralgia, psychiatric symptoms, hypotension, hypoglycemia

- For further details on how to perform HPA axis tests consult with a local endocrinologist. A practical guide is also available in Table 8 of the following article by (Liu et al. 2013)

Omalizumab (Monoclonal Antibody Therapy)

- We have developed a clinical recommendation document, which provides further information about omalizumab therapy

- Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody therapy is PBS approved for severe allergic asthma

- Licensed for children >6 years of age

- Must be a patient of a hospital and a paediatrician

- Only available as an add-on to optimised ICS/LABA therapy (unless contra-indicated), if poor control persists despite optimised treatment

- Multiple trials show efficacy reducing steroid dose, improving asthma quality of life scores, and reducing exacerbations

- Safe in children with few adverse effects (Licari et al. 2014)

- Strict PBS criteria exist for prescribing and prescription. The following links provide information for:

Mepolizumab (Monoclonal Antibody Therapy)

- We have developed a clinical recommendation document, which provides further information about mepolizumab therapy

- Anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody therapy is PBS approved for severe eosinophilic asthma

- Licensed for ≥12years of age

- Requires documented blood eosinophil counts > 300/mL

- Only available as an add-on to optimised ICS/LABA therapy (unless contra-indicated), if poor control persists despite optimised treatment

- Limited data is available in adolescents, but exacerbations rates were reduced and OCS dose reduction demonstrated (Blake et al. 2016).

- Strict PBS criteria applies. Application information is available here

- Uncertain, but possible increased risk of cancer development. This is of concern because of potential length of exposure time if commenced in younger age groups (Roufosse et al. 2013).

Theophylline

- Can be used as an add-on therapy to ICS, however LABAs have been demonstrated to be more effective

- Previously used as a steroid-sparing agent, it is limited as a regular medication due to risk of toxicity

- Has been shown to be useful in severe asthma in adolescents; although rigorous trial data is lacking (Barnes 2010).

- A narrow therapeutic index exists (10-20mg/ml), with wide interpatient variability in drug clearance

- Side effects, especially nausea, are common.

- There is a possibility of toxicity, if levels are not monitored. Toxicity signs include vomiting and abdominal pain, seizures, coarse tremor; major toxicity being seizures and cardiac arrhythmia, hypokalemia hypercalcaemia and hyperglycemia.

Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist (LAMA) - Tiotropium

Promotes bronchodilation and increases airflow. Evidence in a paediatric population demonstrated that tiotropium treatment for moderately severe asthma improved lung function (FEV1), with non-significant trends towards improved asthma control and health-related quality of life (Hamelmann et al. 2016, Szefler et al. 2017).

In Australia, tiotropium by mist inhaler is PBS-listed as an add-on treatment to ICS and LABA for severe asthma in patients:

- Aged 6-17 years

- Under the care of a respiratory physician, paediatric respiratory physician, clinical immunologist, allergist, paediatrician or general physician experienced in the management of patients with severe asthma

- That have failed to achieve adequate control with optimised asthma therapy, despite formal assessment of and adherence to correct inhaler technique, which has been documented AND

- Must have experienced at least one severe exacerbation which has required documented use of systemic corticosteroids in the previous 12 months while receiving optimised asthma therapy OR

- Have experienced frequent episodes of moderate asthma exacerbations AND

- The treatment must be used in combination with a maintenance combination of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) unless a LABA is contraindicated.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

- Methotrexate, ciclosporines and azathioprine have been reported in case series as “steroid-sparing” agents, but limited data on efficacy is available.

Continuous Subcutaneous Infusion of Terbutaline (CSIT)

- Utility was demonstrated in a small case series of severe/difficult asthma in children requiring oral corticosteroids, with clear clinical improvement in some children (Payne et al. 2002). Trial data is lacking.

- Methodology:

- Infusion delivered through insertion of butterfly or infusion set

- Dosing between 2.5–5 mg/24 hr, increasing to a maximum of 10 mg/24 hr as indicated and tolerated

- Treatment is given for a minimum of 2 months, to assess response

Last Updated on