Bronchiectasis Impacts:

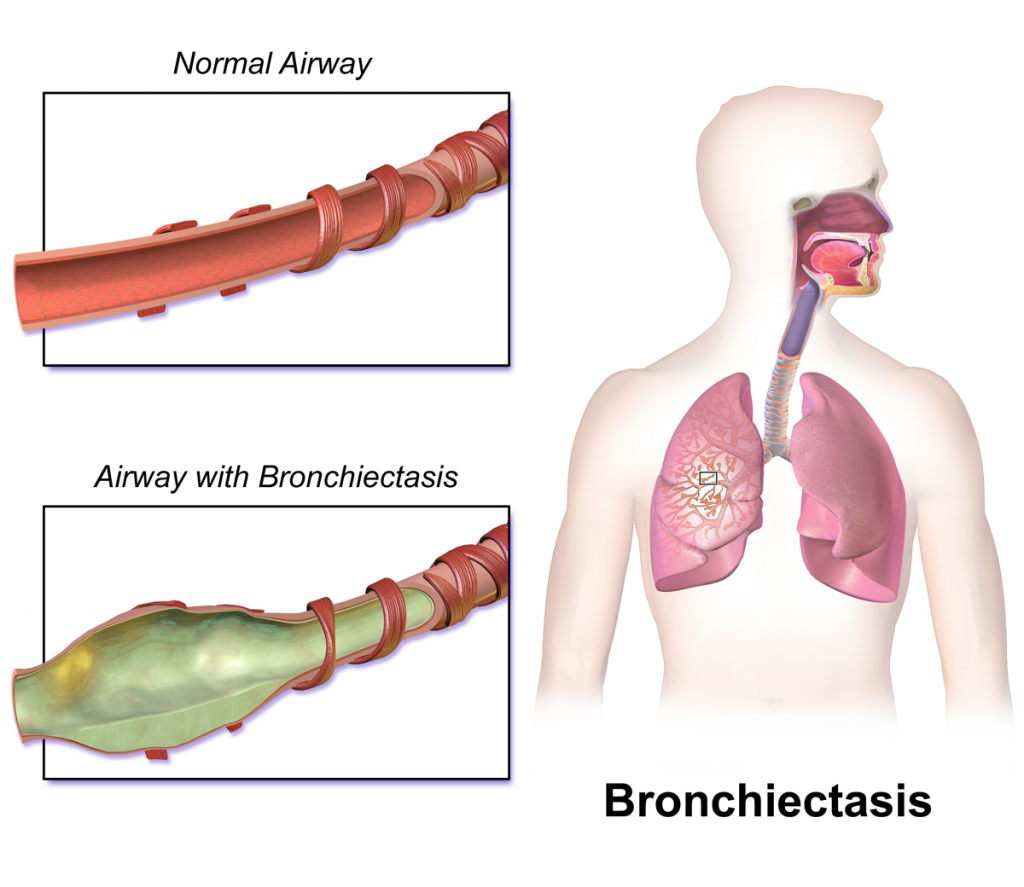

Bronchiectasis refers to the chronic enlargement of the airways, which is associated with chronic cough, expectoration and a tendency to increased infection susceptibility (McShane et al. 2013). Bronchiectasis results from loss of elastin, muscle and cartilage within the lungs, fibrosis of bronchial walls and peribronchial changes. Bronchiectasis can develop as a result of chronic lung disease, following respiratory infection or as a result of primary or secondary immunodeficiency (Bronchiectasis Toolbox).

Prevalence

Prevalence in severe asthma ranges between 24-40% (Porsbjerg et al. 2017), which is markedly higher than ~3% in the mild asthma population. In the general population, bronchiectasis prevalence is higher in females and the elderly (Seitz et al. 2012, Quint et al. 2016).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is determined using high-resolution CT imaging of the airways. A confounding factor is the detection of dilated airways in severe asthma patients without clinical features of bronchiectasis. In some patients, the radiological findings may represent severe asthma, rather than true bronchiectasis.

Impact on Asthma

Individuals with asthma and comorbid bronchiectasis experience:

- More frequent exacerbations and hospitalisations (Coman et al. 2018)

- Worse airflow limitation (Kang et al. 2014)

Bronchiectasis Treatment

Management focuses on airway clearance, using specific physiotherapy techniques, aerobic exercise, and adequate hydration. Inhalation of hyperosmolar agents and low-dose macrolides are also beneficial (Wong et al. 2012). In contrast to asthma attacks / exacerbations, bronchiectasis exacerbations require effective antibiotic therapy, ideally guided by sputum culture (McShane et al. 2013).

Coexisting bronchiectasis and severe asthma may also be associated with concomitant gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and increased bood eosinophil counts (Coman et al. 2018). Where these factors co-exist, they should also be appropriately managed.

Despite the relatively high prevalence of bronchiectasis in people with severe asthma, there is limited evidence on whether effective management improves asthma symptoms.

Additional Resources:

Last Updated on